Bothingone Village, Myanmar

At 69, deputy village chief and Water Management Committee (WMC) chairman U San Yee is remarkably agile and energetic for someone his age. Dressed in a traditional Burmese longyi, he cheerfully led the way from the wooden jetty to the village, unbothered by the blazing sun and blistering heat. Beneath our feet, the soil was parched and cracked, and I could feel the heat radiating through the soles of my sandals.

Like many other villages in the south of the Ayeyarwaddy region, Bothingone village experiences an annual dry season of sparse rainfall that lasts for about 5 months. During this time, the only rudimentary rainwater harvesting pond in the village often dries up, leaving villagers with just a handful of hand-dug tube wells and pumps to obtain clean water for consumption. Sometimes, they have to travel to neighbouring village of Sarchet to collect water with jerry cans. It is common for villagers to ration water use during the dry summer months.

The existing pond in Bothingone village, which is the villagers’ main source of clean water. During the dry summer months, this pond sometimes dries up.

Jerry cans used to collect water

One of U San Yee’s grandchildren playing near the jerry cans.

As the chairman of the Water Management Committee, U San Yee was determined to tackle the water challenges and improve the villagers’ access to clean water. Under his leadership, the village made a unified decision to increase the catchment capacity of the existing pond to help tide them through the dry summer months.

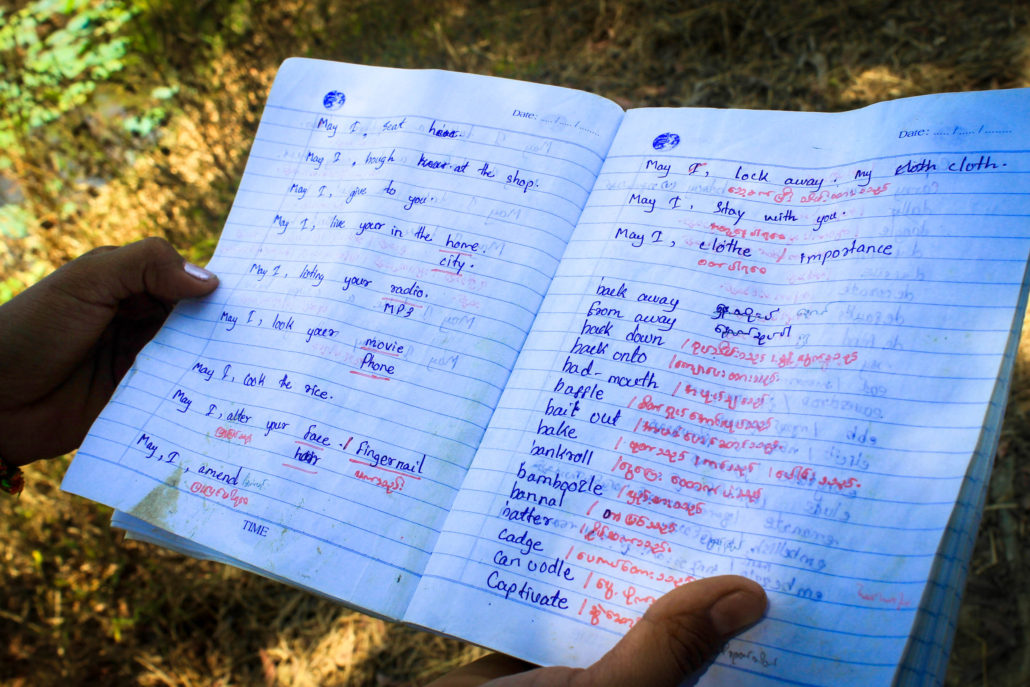

Besides being a village leader and water champion, it turns out that U San Yee is also an aspiring writer and poet. Having experienced and survived the devastation of Cyclone Nargis, he decided to use poetry as a means to educate fellow villagers about the importance of protecting water resources and to encourage them to respect nature. As we sat down inside his home, he took out a notebook, and proudly showed us the poem he had penned.

U San Yee’s poem in Burmese.

This is the English version of the poem*:

Climate changes due to the unbalanced ecosystem,

followed by various natural disasters.

Do not regret only when you suffer such disasters.

Preparation with careful consideration,

will lead to peaceful deliverance of such disasters.

A united effort would breed resilience and sustainability.

Practise continuously,

to create a beautiful environment.

With optimism for the future,

by handing down these good practices to our children.

Dear fellow citizens,

be prepared and observant of

climate changes due to the unbalanced ecosystem.

With the effects of severe heat

and drought that resembles

A child without a mother, a fish out of water –

troubled and deprived,

Be prepared and observant.

If only to be awaken by a deep regret,

as helplessness leads to further errors and degradation

with lives at stake.

*This is an unofficial translation and provided for reference only.

U San Yee’s support and influence proved to be paramount to the successful implementation of the clean water project in Bothingone village. Earlier this year, rehabilitation works to expand the capacity of the existing village pond began. When completed, this project is expected to enable over 1,000 villagers from 220 households to gain better access to clean water.

Construction to expand the capacity of the existing water catchment pond began earlier this year.

Close to the end of our visit, I asked U San Yee about his hopes and dreams for his grandchildren, as well as his advice for the younger generation. He left us with the following words of wisdom:

“My wishes are very simple. I hope for my grandchildren and great grandchildren to be healthy and educated. I hope they travel out of the village to explore the world outside. For the younger generation, my advice would be to stay healthy, build family unity and practise lifelong learning.”

U San Yee with a few of his grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Some of U San Yee’s grandchildren and great grandchildren.

This project in Bothingone village, Labutta township, Myanmar is implemented as one of Lien AID’s pilot clean water projects in the Ayeyarwaddy region.